Advancing a Culture of Belonging

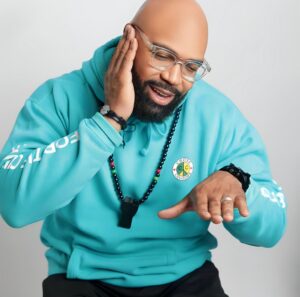

Lee A. Williams II, Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

“You’re smart for a Black kid.”

“You don’t talk like other Black kids.”

“I wish other Black kids were like you in school.”

The words I heard as a Black teenager who went to a predominantly white high school, taking all honors and advanced level courses, still echo in my brain. While these are words no Black child should ever hear, in a public education system that historically and continues to marginalize Black and brown children, it is no surprise that this phrase is still uttered today in classrooms around the country.

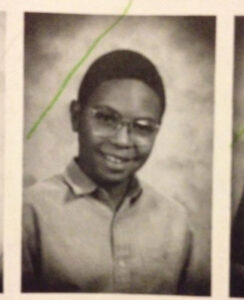

The first 10 years of my life were spent on and off a military base in Germany with my family and being in a classroom where I was one of the very few Black kids. When my family moved back to Fayetteville, North Carolina, it was the first time I ever attended an all-Black elementary school. This was a big culture shock for me. I remember attending my first day of school wearing tight blue jeans with a button down blue Hawaiian shirt tucked in, a belt, and Nike sneakers laced up tight. I immediately didn’t fit in and was teased. I realized that I was neither white enough to be considered white, nor dark enough to be considered Black. My only saving grace was my basketball skills, the only way I could make friends.

Back then, and still true today, the zip code you live in determines the quality of education you receive. My parents knew that the only way I could receive a high-quality education is if my family moved to a richer, whiter neighborhood. In my majority-white school, I didn’t feel accepted – rather, I felt tokenized as one of the few Black students because of my athletic abilities, which feeds into a common stereotype about Black boys. I struggled with my self-confidence, especially about my name. I would sometimes go by LeAndre instead of Lee because I felt it was a stronger, more masculine and Black name than Lee in a misguided attempt to carve out my identity. In the media, Black men are often portrayed as hard, gangster, and strong, and I felt like if I didn’t fit that stereotype, I wouldn’t be accepted by anyone.

Throughout my education, I would often encounter racism but not knowing it was called racism. Not knowing what to call it when a white educator stereotyped me as “one of the good ones” or when my white college professor told me not to go to office hours because she was afraid to help me alone. Racism leaves a scar on all of us who endure it. Although I did not have the words to describe racism as a child and as a young man, I knew the pain I felt was real.

When I was rejected by BET at age 21 in my quest to become a hip hop artist, I had to find another way to speak truth to power. A close friend of mine, who was a music teacher at the time, invited me to her class one day. And that is when I realized that as a teacher, you can make your classroom your stage. So I decided to teach English, and the rest was history, engaging students in my class with the music and poetry of hip hop.

As a classroom educator, I saw the potential in my students, far beyond how Black students are typically regarded. When I became a school leader, I was often sent to Title I schools to act as a “disciplinarian” for Black children, especially Black boys. District leaders didn’t understand why I was so successful with Black students; it wasn’t because I was strict but rather because I built deep relationships with my students. I led with love. Because of this, I still felt like I was not working to fix the root of the problem, and I wanted to deepen the impact of my work – and to do that, I had to work on dismantling the system of oppression educators, families, and students alike were facing. That’s when I shifted my focus to education equity.

So why Rocketship? When I worked at an organization dedicated to helping 17 and 18 year olds who were at a freshman level graduate high school, I realized I was too late – to really tackle the root of the problem, I needed to go to the beginning. Elementary school is already when we can determine the trajectory of a student’s life. Data shows that 3rd grade literacy scores can indicate whether someone completes high school, goes to college or goes to prison. So the best way to really disrupt the school-to-prison pipeline is eliminate systemic barriers in the earliest years of education for our historically underserved children. It’s also why our literacy work in and of itself is social justice.

I’m excited to be at Rocketship because we are all in the right space to really disrupt systems of oppression, and I look forward to making that vision a reality. It starts with our people – the inclusion we can create for all of the educators in our organization – and it continues into our classroom and our communities.

Published on February 23, 2024

Read more stories about: Uncategorized.