How I Became a Reformer

by Mary Moran, Co-founder and Executive Director, Our Voice Voz Nuestra

What is the state of education in New Orleans ten years after the storm? Like crawfish boils in the spring, this question has become a staple in the social lexicon of families, teachers, church mothers and reformers in New Orleans. Responses to the question, more often than not, lead to a more complex set of conversations about crime, violence, prisons and the lack of opportunity. The proximal relationship I have to each often prompts a reflection of my own childhood experiences with these interwoven systems and helps explain how and why I became a reformer.

Something we did regularly as a family was take long drives and stand in long lines to visit my older brother who has cycled through prison systems since 1997 – the same year Master P dropped his biggest single, “Make ‘Em Say Uhh!”. Rudy, who was incredibly charming and talented as a young boy, became a man in a California penitentiary. Week after week, we would see the same families visiting their boys. These families were black, Latino, Asian, white and oddly, well organized. Whether standing in line to receive a visiting number, or while waiting for the bus to take us to the secure visitation area, we organized. Across language barriers, age differences and gang communities we shared information that ranged from the best drug programs to the most effective (and inexpensive) lawyers. Through tears of disappointment, hopelessness and sheer fear of the unknown, we used our collective experiences and stories to draw strength together. It is here – within an enclave of chaos and dejection – that I became fascinated with the power of organizing and enamored by the willingness of families to toil with, support and uplift each other through commonalities in the fight for their children. Though I haven’t a clue where those families are now, the spirit of their struggle is resonant of the struggle black and brown families in New Orleans have endured over the past ten years to find quality schools for their kids. As an organizer who believes in reform as a lever of equity, it pains me to witness such disparate institutions – prisons and schools – produce such homogenous outcomes.

In 2012, Cindy Chang and the Times-Picayune put out an eight part series, “Louisiana Incarcerated: How We Built the World’s Prison Capital”. Something I learned then has always stayed with me: the typical lifer (prisoner with a life sentence) enters Angola at 25 years old. With all of the rage and sadness that overwhelms me by that fact alone — I think about the opportunity our families, communities and schools have for at least 13 years of their lives. I think about the thousands of families who serve the same time as their children without ever entering a prison cell. I think about the trajectory of our schools since Katrina and I’m reminded that the odds we face in creating a more equitable education system is the glue we need to piece together our communities, our strength and our love for the children of the city.

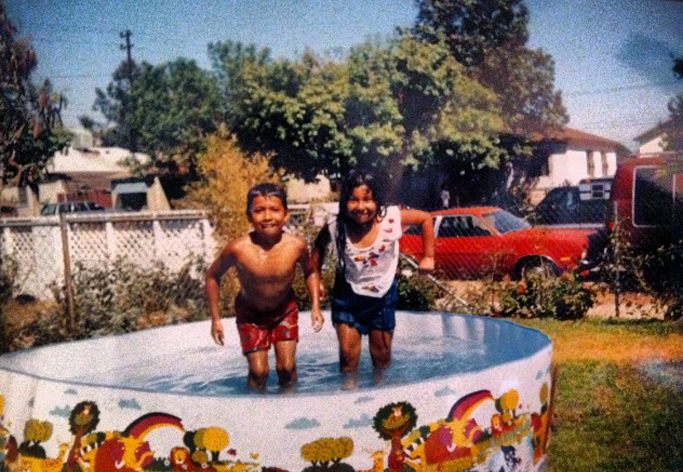

I understand firsthand the risks of not improving the quality of schools and what that does to families and communities. As we look forward to the next ten years of reform, it is important to recruit teachers who are from New Orleans – who understand these risks and who in addition to providing the academic rigor our students need also understands how to motivate and inspire our children. If the schools my brother and I attended had a standard of academic rigor, a culture of scholarship that translated culturally to me and my peers and that were inclusive of our community and traditions – other possibilities could be imagined for my brother’s life trajectory and so many other young people like him. The vision moving forward needs to be created with teachers, parents and students and should include a deliberate plan that disrupts the school-to-prison trends in the state. Since Hurricane Katrina there has been an influx of the Vietnamese and Latino population in the city. Our vision must include voices from the Vietnamese and Latino community and include the issues affecting their children. Sustaining the education reform movement can only happen when children’s best advocates – their parents – are active participants in changing the systems, policies and community’s engagement with schools.

“How I Became a Reformer” was originally published on Second Line Education Blog. It has been republished on Beyond with the permission of the author.

Published on May 20, 2015

Read more stories about: Education Reform.